Written by Derek King, an Architectural Historian in Buffalo, New York.

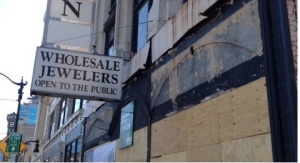

There is a type of building construction where the exterior of the main elevation, or façade, is preserved, while the rest of the building is demolished, and rebuilt with modern materials and design. It’s most often seen in downtown settings, where developers want to (or are forced through design standards) maintain the historic appearance of the original structure, while still doing whatever they want with the building’s interior.

In architectural terms, this is called “facadism.” It’s an illusion really; giving the appearance of preserving historic materials, while in reality, it only goes skin deep. For historic preservationists, it’s almost as bad as wholesale demolition; it gives a false representation of the building’s history, and worse, loses all the economic and environmentally sustainable aspects of preservation.

For those of you who were unable to attend the public meeting regarding the Outer Harbor on Tuesday night, you missed one of the best examples of democratic facadism. Though the plans Perkins + Will unveiled had only a few problems (though those few were glaring), what the meeting exposed about the public process in our city, region, and state, was far more troubling.

The Outer Harbor Plan

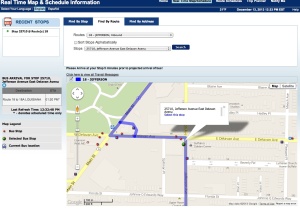

First, the plan. Overall, Perkins + Will’s latest draft plan features a lot of great ideas. Redevelopment around Terminals A+B, a Great Lakes Park featuring research and environmental preserves, new connectivity to Buffalo’s roads, restaurants and night life, and even mass transit to improve access to our greatest resource. The problems, as elucidated in this article on the Buffalo News, were largely tied to the creation of “neighborhoods” and the location of one of them right next to the Times Beach Nature Preserve, one of our region’s most important ecological nodes.

Let’s tease these out a little bit. First and foremost, any residential development on the Outer Harbor will lead to significant cost to the taxpayers, with little benefit. This cost will be in the form of constructing sewer, electric, and road infrastructure, and then maintaining it, for years to come. That includes plowing, and any other winter repairs, in the coldest and snowiest part of our city, when Buffalo already has trouble keeping up with maintenance elsewhere. Does Buffalo need new “neighborhoods” when it can’t even keep up with the roads in the communities that already exist?

That being said, some development makes sense, particularly around Terminals A +B, where infrastructure is already established, but any construction north of there will saddle taxpayers with the cost of construction and repair. What is the difference between building high-density neighborhoods on the Outer Harbor and building one on a former golf course in Amherst? Won’t the costs of constructing and maintaining these enclaves siphon off a lot of the revenue they will supposedly generate for a park?

So if the justification of residential development is that it’s needed to pay for a park, but much of the return will be needed to maintain the infrastructure for these new developments, what is the benefit to the public? New housing units? Won’t this take away from the resurgent housing markets in Elmwood and Downtown?

And who will be able to live there anyways; Noah Friedman noted in the BN article that the public sessions do not reflect “the other folk…that I see on the street.” Considering the median household income in Buffalo is $30,502, with an unemployment rate over 10%, which folks from “the streets” was he marketing these houses to? Indeed, the “older and whiter” demographic Mr. Friedman was noting seemed to be the exact population Tom Dee, president of ECHDC, was targeting; after the presentation, he remarked that appealing to empty-nesters and babyboomers from the suburbs was one of the driving factors for including housing on the Outer Harbor.

Does the public benefit from building new “neighborhoods” to compete with the ones we already have? Friedman mentions Elmwood and Allentown as inspirations for the density found in the “Ship Canal” and “Cultural” districts; aren’t these places the “neighborhoods” you’d be drawing potential young residents and consumers from? Will it really benefit Buffalo to create new neighborhoods that steal residents and business from the neighborhoods that are currently surging, and even more importantly, when we have other neighborhoods that could use some of this infrastructure investment more? I can think of plenty of neighborhoods on the East and West Sides that would benefit from new roads and sewers before we consider building new neighborhoods that draw even more people and investment from our communities.

Now, leaving aside the fact that the Outer Harbor is already an incredible open space with free public access to the water (indeed, the biggest problem currently is actually getting there), the “Great Lakes Park” concept is very cool. The research facility, the “blue economy” concept, and the city beach are all huge plusses for this space. If some residential development is necessary, then building it around the existing infrastructure near Terminal A + B to begin creating such a wonderful asset to our community should definitely be the first phase of this project.

But what about the other phases? The Perkins + Will team laid out two 20 year “phasing plans” to roll out their development scenarios, but didn’t take into the consideration the fact that 20 years from now, we might have a very different Outer Harbor to work with. Suppose that the estimates to repair the Skyway are true ($117 over the next 20 years, back in 2012), shouldn’t any long-term plans for the Outer Harbor consider the possibility of its complete removal? They did include a lift-bridge in their plan connecting to Main Street, but did not include the 45 acres that would be available for development if the Skyway and elevated portions of Route 5 no longer existed.

Simple GIS Map showing land available for redevelopment if Skyway and elevated portions of Route 5 were used for residential.

Consider this phasing: Construction of the Great Lakes Park in conjunction with the development of the “Heritage Lofts” neighborhood around Terminals A and B, but refraining from any development north of there (particularly around Times Beach) until the questions regarding the Skyway/Route 5 and Main Street Bridge are settled, at which point many of the plans the firm proposed could be moved east of Fuhrman Boulevard. Considering their plans already accounted for 20 years of roll out, this could be a win-win for everyone; the public doesn’t lose already open and free access to the water, we don’t have unnecessary residential development adjacent to a nature preserve, the ECHDC still gets to see development on the Outer Harbor to pay for our new park, and as a city we can turn space wasted by an superfluous highway into land for tax generating development.

The Bigger Issues

As mentioned, there are much deeper issues tied to this process, much of it related to structural inequality, but some built into our political system. The interactions with consultants and ECHDC representatives during Tuesday’s meeting highlighted these glaring problems with the Outer Harbor planning process, and with our City and State’s democratic process as a whole.

Some of these problems have already been discussed: the lack of foresight relating to the biggest piece of transportation infrastructure currently on the Outer Harbor, the cruel suggestion that the majority of Buffalo would support housing on public land they could never afford themselves, and the negligent allocation of resources that would negatively impact crucial wildlife sanctuaries and divert infrastructure investment from other parts of the city.

The deeper problems lie in the political process, and were elaborated to me by Noah Friedman himself in a not-so-pleasant way. Before my interaction with him, however, I spoke with Tom Dee, the President of ECHDC, and Jaime, the economic consultant on the project.

After the presentation, I spoke with Mr. Dee, who expressed his own opinions about the Outer Harbor, namely that he didn’t think its current state was “good,” that people weren’t using the space, and suggested that Times Beach Nature Preserve was underutilized, asking, “How many people even visit Times Beach? 500 a year?” His reactions were expected; he’s the head of an organization with the words “Development Corporation” in them, so naturally, undeveloped space (no matter how much it’s already used by bikers, fishers, kayakers, and picnicking families), is not his concern except for its potential as a revenue stream. Mr. Dee concluded our discussion by saying, “I guess we’ll just have to agree to disagree,” to which I replied, “That’s true, but the difference is that you have a lot more say in this process than I do.” He pointed to the rear of the room, where displays outlined the proposal’s components in depth and said this was my chance to have my say.

Shortly after, I spoke with Jaime, the economic adviser. Unfortunately, I did not get his last name, but we spoke very candidly about our opinions on the project. Like Mr. Dee, his biggest concern was having the largest economic impact for the city, and played devil’s advocate with me regarding my criticisms of the project. After about ten minutes, we came to a loose agreement, compromising with a plan similar to the phasing scenario I outlined above. Overall, as with Mr. Dee’s conversation, it was a very respectful interaction with differing opinions and possible solutions. Encouraged by this, I tracked down Mr. Friedman to discuss how this type of scenario could be implemented.

Now, I’d like to preface this by saying that I have been volunteering with 21st Century Park for the last year, and had interacted with Mr. Friedman at the previous session to bring up some of my concerns. When we spoke Tuesday, it was at the end of the program, just 15 minutes before input session ended, and I’m sure that he had been bombarded by my colleagues at 21st Century Park, and the numerous other advocates (several quoted by BN) who had brought up the discrepancy of going from 7% public support for housing, to a plan with what appeared to be 30% housing related development.

Having talked with Mr. Friendman about this concern at the previous meeting (the 7% figure was used in both Tuesday’s and August’s presentations), I figured he was a good person to revisit the conversation with. I barely finished my sentence however, before he began an aggressive rebuttal, lumping me into a group of “park people,” belittling my opinion, and in general, addressed my concerns with contempt that at times alternated between condescension and outright rudeness.

His attitude aside, which I’m sure can be attributed to a long night where numerous people had likely aggressively voiced their opinions about his team’s plans, he did make a lot of great points. For instance, he noted that P+W’s plans conformed to the “Green Code”, the new zoning and building code created by the city, and actually featured a lot more open space than the Brownfield Opportunity Area plan for the Outer Harbor, which had much more residential development. He went on to insinuate that it was my fault, and my fellow residents, if we didn’t change those two plans, and thus our problem, if we didn’t like how that shaped P+W’s design.

When I pointed out that I had gone to those meetings, and along with many other residents, expressed concerns similar to the ones related that night, he lumped me back into the “park people,” saying we thought our opinions were the only ones that mattered, but that there were plenty of other people who, just because they didn’t stay as long, or talk as much, had input to consider. Even then, he noted, repeating nearly verbatim the quote from the Buffalo News, “We did not say we would absolutely stick to [the public input] and make that the plan.”

Though I was upset by the interaction, Mr. Friedman raised a lot of points that made me angrier beyond his unprofessional treatment of my concerns. For instance, the President of ECHDC indicated that these public sessions are opportunities to have our voices heard, and then the consultant said that the workshops are formalities, that they are going to disregard the very data they collected, to design for “all of Buffalo.”

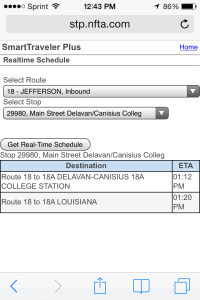

Let’s put aside the fact that their design included waterfront housing for “all of Buffalo,” that will likely be out of the price-range of “nearly all of Buffalo,” to focus on Mr. Friedman’s concerns about the demographics of the meeting. Forgetting that it reflected one of the demographics Mr. Dee was hoping to target (babyboomers and empty nesters), you cannot lament poor representation when you announce a meeting one-week before it occurs, located downtown in one of the most difficult spots to arrive by public transportation and walking, in the middle of the week, and at dinnertime.

It’s laughable, and almost hypocritical, that Perkins + Will says their design is “for all of Buffalo,” and is concerned about demographic representation when they choose a poor location, with short notice, and limited exposure, and most importantly, chose to ignore the data they collected at meetings they held in some of Buffalo’s most diverse neighborhoods (their July 10th planning meeting was at the Makowski Early Childhood Center near Masten Park).

Now, one additional comment by Mr. Friedman was exceptionally troubling. After remarking, once again, that they were designing for “all of Buffalo,” he noted “all” included not just the participants in the sessions, but the city’s developers, and the ECHDC. He once again implied it was my fault if I disagreed with the plan, since it was my elected officials who selected the board of the ECHDC, and my elected officials who drafted the Green Code, and if I had such a problem with it, maybe I should elect different representatives.

So here we are, at the crux of the problem with the Outer Harbor planning process. It’s not Perkins + Will, which as Dana Furman-Saylor noted in the BN article is a good firm with national experience, and who at the end of the day are just trying to do their job, so of course they would be upset having to deal with passionate citizens, some of whom may criticize their work.

Mr. Friedman is right: it is our fault that we have a government in Albany more concerned with development dollars than the actual quality of life issues in its cities; it is our fault that ECHDC, a subsidiary of the “public authority” Empire State Development which is exempt from state and local regulations, is allowed to dictate the use of public land, since we did elect politicians who selected the board; it is our fault that our local government seems hell-bent on imitating San Francisco, New York City, and Chicago, when we don’t have the resources, population, or leadership to justify those comparisons; and lastly, it is our fault that we allowed public discussion regarding the Outer Harbor to be divided by three separate planning entities (the ECHD and P+W, the BOA, and the Green Code), culminating in a rushed four-month planning process that will shape the next 20 years for our city’s most important resource.

Rebuilding and Preserving

So where do we go from here? Clearly it is not to public input sessions, because if this planning process is any indication, the voice and opinions of the public are just there for “consideration,” and not for actual implementation. It must not be City Hall, because the owner and driver of this planning process is ECHDC, who answers to the Empire State Development Corporation. Who do they answer to? Albany? Don’t they answer to the voters?

Imagine my frustration as Mr. Friedman outlined this circuitous route, avoiding my concerns with the plan all together, to put the onus of responsibility back on me. Somehow, being the “public” meant my voice didn’t matter at “public meetings,” but simultaneously meant it was my responsibility to ensure that quasi-private entities like ECHDC were kept to task… just not at the input sessions they were hosting.

Lets put this all together: ECHDC plans a meeting with only a week of notice in a place where it’s difficult to attend, and P+W says the demographics of attendees are not representative of Buffalo, despite designing a plan for the demographics of Seattle, that eliminates public space and doesn’t incorporate a plan for the future of the Skyway, and adds neighborhoods, one of which abuts a critical international nature preserve, to a city that can’t even help the neighborhoods it has and will compete with those just beginning to thrive, and it’s my fault if I don’t like it, even though my only recourse is to vote for the people who vote for the board that makes decisions, to which I can give input that won’t be listened to.

So, in the end, I was pretty angry about Tuesday’s Outer Harbor Public Input session. Not with the plan itself, since over half of P+W’s design I’m actually very excited about, or even the firm itself, which has hosted planning sessions that were better than most other planning sessions I’ve been a part of in Buffalo, and whose staff has been exemplary, with the exception of one interaction that was probably catalyzed by stress and frustration (and likely also by some of my more obstinate fellow residents, “park people” or not).

With facadism, there’s no going back. Once the interior is gone, that building has lost its historic integrity, and it’s all just an illusion. You walk through the doors, and it all feels wrong; you can tell that the bones don’t fit the skin, that someone reworked this building to get what they want, and how they wanted it, history (and the people that history belongs to) be damned.

Here in Western New York, we get to vote, and “participate,” but when it comes down to it, we only get democracy on the surface; we get to write on sticky notes, and vote on concepts, but once you get through the walls, you realize someone has reworked the system so they always get what they want, and how they want it. With the Outer Harbor, no matter how few members of the public supported it, we’re going to get large-scale residential development on our waterfront.

On Tuesday, we got to be a part of the planning process on the surface, but behind closed doors, someone ripped out the guts of our democracy. According to Noah Friedman, it’s our fault we didn’t stop them, but unlike with facadism, where you can see the building being demolished just a few feet beneath the surface, the erosion of our democracy has been subtle, and we’re left with a system that’s been reconstructed to suit someone else’s needs.

I don’t blame Perkins + Will for the problems with this plan anymore than I blame the citizens of Buffalo for the problems with our system. I don’t blame any one person or entity at all—but I am angry that the system is broken, and I am angry with the fact that in the end, the session showed just how little say the public has over the future of our city, and how difficult it will be to reconstruct a process that’s been gutted.